Table of Contents

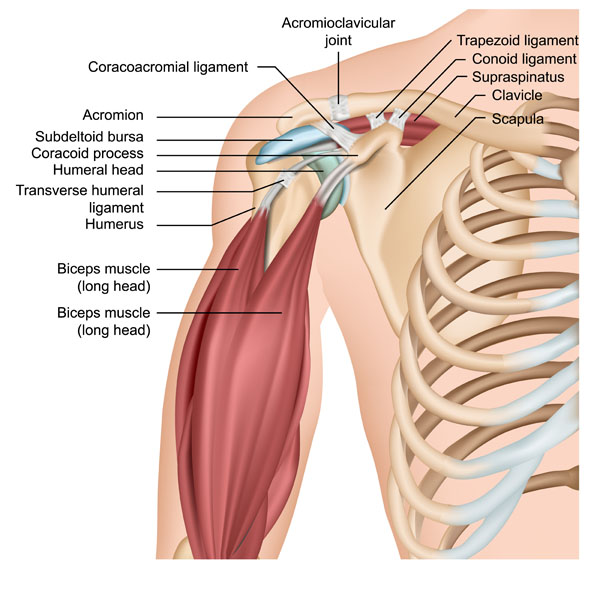

Shoulder and Upper Arm Anatomy

This image illustrates the anatomy of the human shoulder, highlighting various bones, muscles, ligaments, and joints. At the top, we see the acromioclavicular joint, which is where the acromion and the clavicle meet. The acromion is a bony process that protrudes from the scapula, providing an attachment for the coracoacromial ligament. This ligament forms a protective arch over the shoulder joint.

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is a triangular bone that connects with the humerus and clavicle. The clavicle, or collarbone, is a long bone that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum, providing structural support. We can also see the coracoid process, another protrusion of the scapula, which is important for muscle attachment.

Underneath the acromion, there is the subdeltoid bursa, a fluid-filled sac that reduces friction between the muscles and bones during movement. The humeral head, the top part of the upper arm bone, fits into the socket of the scapula to form the shoulder joint.

The image also shows the biceps muscle, specifically the long head of the biceps, which runs in front of the humerus and attaches to the top of the shoulder socket. The transverse humeral ligament holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps in place.

Moving to the ligaments, we have the trapezoid and conoid ligaments, which are part of the coracoclavicular ligament that connects the clavicle with the coracoid process. These ligaments help stabilize the clavicle. Lastly, we see the supraspinatus muscle, which is one of the four rotator cuff muscles, and it sits on top of the shoulder, helping to lift the arm and hold the humerus in place.

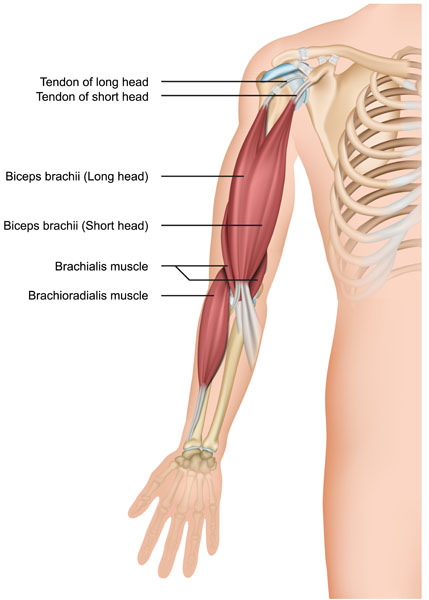

Muscles of Upper Arm and Forearm Supporting Supination

This image presents the musculature of the upper arm and the proximal region of the forearm, focusing on the muscles involved in flexion of the elbow and supination of the forearm.

The biceps brachii muscle is shown with its two heads: the long head and the short head. The long head of the biceps brachii runs along the inside of the arm and originates from above the shoulder joint, while the short head originates from the coracoid process of the scapula. These heads converge into a single muscle belly, which is the prominent bulge when the biceps is flexed. They both insert into the forearm via their tendons. The tendon of the long head is particularly interesting as it passes inside the shoulder joint, contributing to the stability of the joint.

Beneath the biceps brachii is the brachialis muscle. This muscle lies deeper and is primarily responsible for flexing the elbow. It is a strong flexor of the elbow, irrespective of the position of the forearm.

On the lateral side of the forearm, you can observe the brachioradialis muscle. This muscle originates from the lower part of the humerus and crosses the elbow to attach to the radius, one of the two bones of the forearm. The brachioradialis assists in the flexion of the elbow, particularly when the forearm is in a mid-position between pronation and supination.

These muscles are critical for various movements of the forearm and hand, including lifting and grasping objects. The tendons of the long and short heads of the biceps brachii are important anatomical landmarks and are often palpated in clinical examinations of the arm.

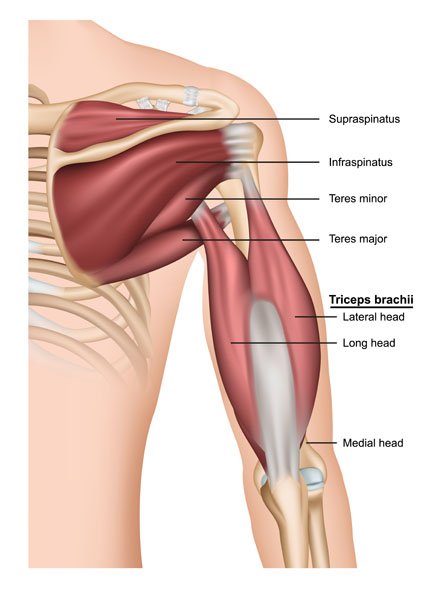

Posterior Aspect of the Shoulder and Upper Arm

The image provides a detailed view of the posterior aspect of the shoulder and upper arm, highlighting the muscles that contribute to shoulder stability and arm extension.

At the top, we see the supraspinatus muscle, one of the four rotator cuff muscles, which is situated on the upper portion of the scapula, above the spine. It functions mainly to initiate the abduction of the arm.

Below the supraspinatus is the infraspinatus muscle, another rotator cuff muscle, which occupies the majority of the infraspinous fossa on the scapula. It is larger than the supraspinatus and primarily works to externally rotate the arm at the shoulder.

Adjacent to the infraspinatus is the teres minor muscle, the smallest of the rotator cuff muscles. This muscle also contributes to the external rotation of the arm.

Directly below the teres minor, we find the teres major muscle, which is not part of the rotator cuff. The teres major assists in the internal rotation and adduction of the arm.

Dominating the lower half of the image is the triceps brachii muscle, which comprises three heads: the long head, the lateral head, and the medial head, not all visible in this view. The long head of the triceps brachii is unique because it crosses the shoulder joint and assists in arm adduction, along with its primary role in elbow extension. The lateral head is located on the outer side of the arm and is involved in elbow extension when the arm is in a position of power, such as pushing away from the body. The medial head, which is partially obscured in this image, lies beneath the long and lateral heads, and it contributes to elbow extension, especially when the arm is in a more neutral or extended position.

These muscles, particularly the rotator cuff group, are crucial for shoulder movements and for maintaining the stability of the glenohumeral joint, which is where the head of the humerus fits into the glenoid fossa of the scapula. The triceps brachii, on the other hand, is key for movements requiring forceful extension of the elbow, such as in pressing actions.

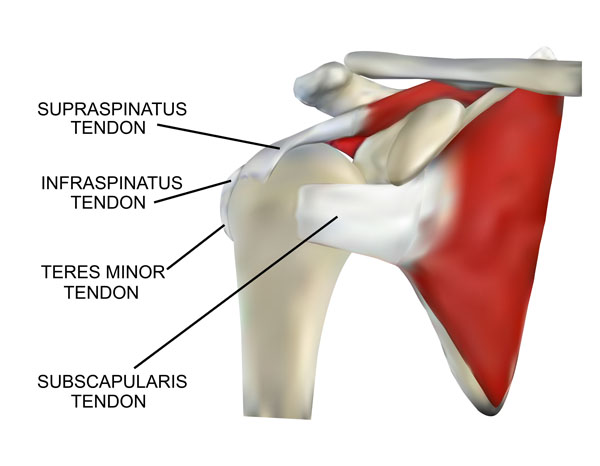

Tendons of the Rotator Cuff Muscles

This image provides a focused view on the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles as they attach to the humerus. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that play a vital role in stabilizing the shoulder joint and allowing for a wide range of shoulder movements.

At the top, we have the supraspinatus tendon. This tendon attaches the supraspinatus muscle, which lies above the spine of the scapula, to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is the most frequently injured rotator cuff tendon, often involved in rotator cuff tears.

Below the supraspinatus tendon is the infraspinatus tendon, which connects the infraspinatus muscle to the greater tubercle of the humerus as well. This muscle primarily assists in the external rotation of the shoulder.

Next, we see the teres minor tendon. This tendon anchors the teres minor muscle to the greater tubercle of the humerus, just below the infraspinatus. The teres minor works alongside the infraspinatus to externally rotate the arm at the shoulder.

Finally, at the bottom of the image is the subscapularis tendon. It is the tendon of the subscapularis muscle, which sits on the anterior (frontal) surface of the scapula. This tendon attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus and functions to internally rotate the arm.

Together, these tendons envelop the head of the humerus, forming a “cuff” that not only helps to rotate the arm but also secures the humeral head within the shallow socket of the scapula, allowing for the complex and multi-directional mobility of the shoulder joint.

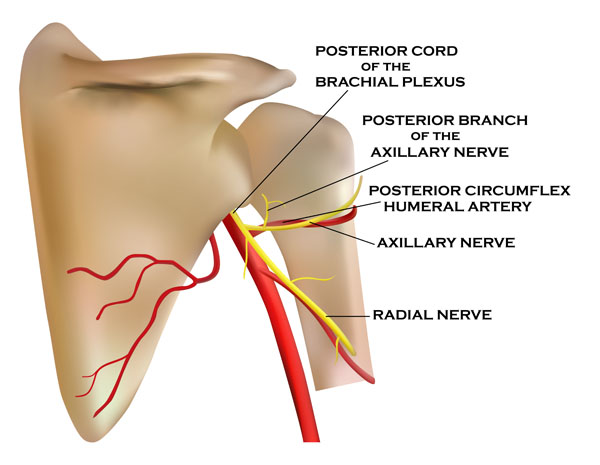

Neural and Vascular Structures of the Shoulder

In this image, we see the neural and vascular structures that are located in the vicinity of the shoulder joint, specifically focusing on the elements of the brachial plexus and associated blood vessels.

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerves that originates from the spinal cord in the neck and travels down to the arm. Here, we see the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, which is one of the three cords that give rise to the terminal branches of the plexus. The cords of the brachial plexus are named according to their position relative to the axillary artery.

From the posterior cord, we see the axillary nerve branching out. This nerve innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles and provides sensation to the skin covering the deltoid region. The axillary nerve is also noteworthy for its vulnerability during shoulder injuries.

The posterior branch of the axillary nerve is shown here as well, which will innervate the same areas as the main trunk of the axillary nerve. Its depiction indicates its pathway around the surgical neck of the humerus, a common site for nerve impingement or injury.

Alongside these nerves is the posterior circumflex humeral artery, which accompanies the axillary nerve through the quadrangular space—an anatomical passage formed by muscles around the shoulder. This artery supplies blood to the deltoid area and the shoulder joint.

Lastly, the radial nerve, one of the major nerves of the arm, is also shown. It originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and travels down the arm to control the muscles on the back of the upper limb, responsible for extending the wrist and fingers. It also provides sensory information from the back of the arm and hand.

The interplay between these nerves and blood vessels is critical for the function and health of the upper limb, enabling movement, sensation, and circulation. Injury to these structures can lead to significant impairment, which is why the anatomy in this region is important for surgical considerations and understanding shoulder and arm pathologies.

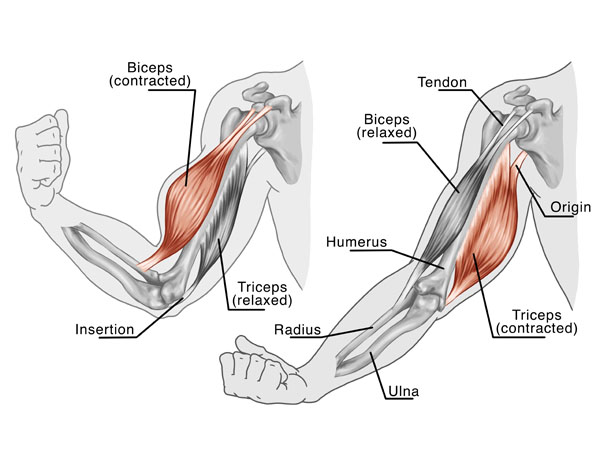

Muscular Dynamics of Flexion and Extension

This image depicts the muscular dynamics of the arm during flexion and extension at the elbow joint, showcasing the biceps and triceps muscles in different states of contraction.

On the left side of the image, the biceps brachii muscle is contracted, pulling the forearm up and resulting in elbow flexion. This action is often referred to as “bending the arm.” The biceps brachii has two points of origin on the scapula and inserts via a tendon onto the radius, one of the two bones of the forearm. When the biceps contract, the forearm is pulled upwards as the muscle shortens.

Simultaneously, the triceps brachii muscle is shown in a relaxed state. The triceps is the antagonist muscle to the biceps during forearm flexion; it must relax to allow for a smooth bending motion. The triceps has three points of origin at the back of the humerus and the scapula and inserts onto the olecranon process of the ulna, the other bone of the forearm.

On the right side of the image, we see the reverse situation during the extension of the arm. The triceps brachii muscle is contracted, which straightens the elbow joint as the muscle shortens and pulls on the ulna. The biceps brachii muscle is now relaxed, allowing the arm to extend. The tendons at each end of the muscles play a crucial role in transmitting the force from the muscle contractions to move the bones of the forearm.

The interplay between the biceps and triceps, one contracting while the other relaxes, is a perfect example of how agonist and antagonist muscles work in opposition to control joint movements. This mechanism is fundamental to almost all voluntary movements in the human body.

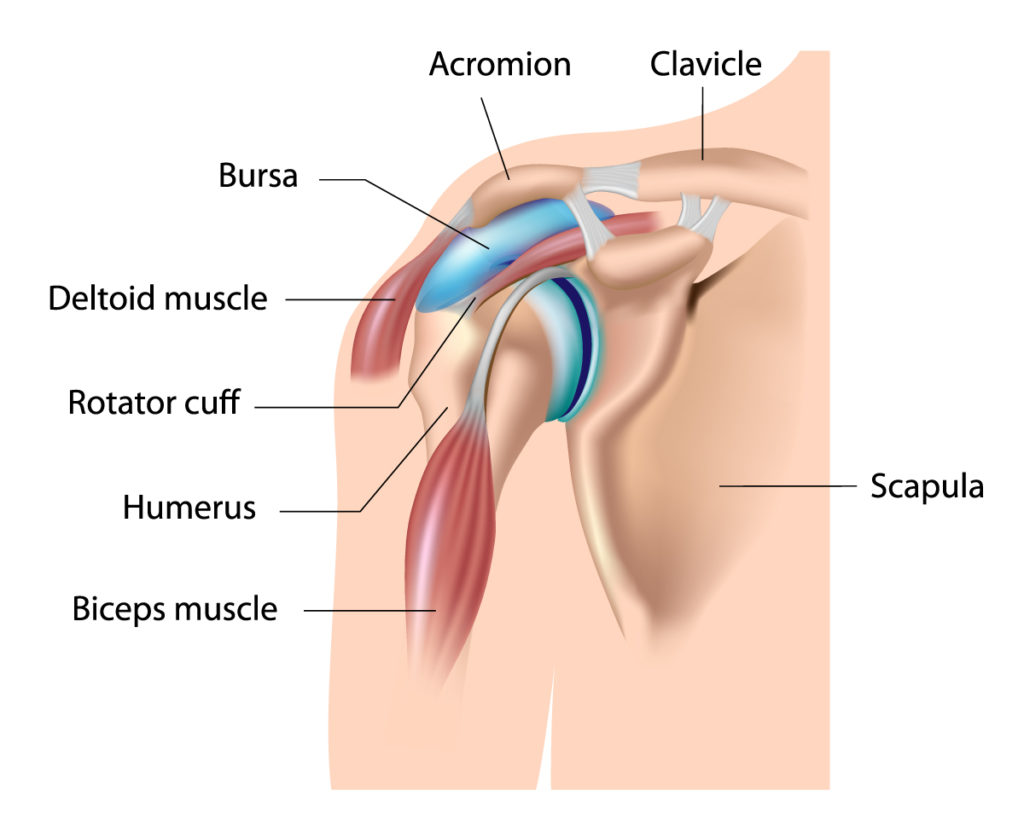

Detailed Shoulder Anatomy

This diagram provides an overview of the shoulder’s anatomy, emphasizing the musculoskeletal and associated soft tissue structures.

At the top, we have the clavicle, commonly known as the collarbone. It spans horizontally across the top of the chest and meets the acromion at the acromioclavicular joint. The acromion is a bony projection of the scapula, also referred to as the shoulder blade, which is a large, flat bone situated in the upper back.

Beneath the acromion, there is the bursa, which is a small sac filled with synovial fluid. The purpose of the bursa is to reduce friction and allow for smooth movement between the bones, muscles, and tendons in the shoulder region.

The deltoid muscle, shown wrapping around the shoulder, is the principal muscle that forms the rounded contour of the human shoulder. Its main function is to lift the arm away from the body and help with overall arm rotation.

Below the deltoid muscle, we can see the rotator cuff, a group of muscles and their tendons that stabilize the shoulder. The rotator cuff is made up of four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles collectively work to rotate the arm and keep the head of the humerus firmly within the shallow socket of the scapula.

The humerus is the long bone in the upper arm, extending from the shoulder to the elbow. It interacts with the muscles of the shoulder to facilitate a wide range of movements.

Finally, the biceps muscle is visible in the front of the upper arm. This muscle is responsible for flexing the elbow and rotating the forearm. It has two heads that originate from different parts of the shoulder and attach to the forearm bones, enabling its function.

Understanding this anatomy is crucial for diagnosing and managing shoulder pain and injuries, which are common due to the complexity and extensive range of motion of the shoulder joint.

Anatomical Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acromioclavicular Joint | The joint where the acromion and the clavicle meet, pivotal for shoulder movement and structural support. |

| Acromion | A bony process on the scapula that provides attachment for the coracoacromial ligament, forming an arch over the shoulder joint. |

| Biceps Brachii | A muscle of the upper arm with two heads (long and short), involved in flexing the elbow and supinating the forearm. |

| Biceps Tendon | The tendon that connects the biceps muscle to the shoulder and forearm bones, crucial for the stability of the shoulder joint and elbow flexion. |

| Brachialis | A muscle located beneath the biceps, primarily responsible for elbow flexion. |

| Brachioradialis | A muscle originating from the lower part of the humerus and attaching to the radius, assisting in elbow flexion. |

| Clavicle | The collarbone, a long bone that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and sternum, providing structural support. |

| Coracoacromial Ligament | A ligament that forms a protective arch over the shoulder joint. |

| Coracoclavicular Ligament | A ligament connecting the clavicle with the coracoid process, consisting of the trapezoid and conoid ligaments, helping to stabilize the clavicle. |

| Coracoid Process | A protrusion on the scapula important for muscle attachment. |

| Cubital Tunnel Syndrome | A condition where the ulnar nerve becomes inflamed or compressed at the elbow, leading to pain, numbness, or tingling in the ring and little fingers. |

| Deltoid Muscle | The principal muscle forming the rounded contour of the shoulder, involved in lifting the arm and aiding in arm rotation. |

| Humeral Head | The top part of the upper arm bone that fits into the socket of the scapula to form the shoulder joint. |

| Infraspinatus Muscle | A rotator cuff muscle located below the supraspinatus, working to externally rotate the arm at the shoulder. |

| Lateral Epicondyle | A bony prominence on the outer side of the humerus to which forearm muscles attach. |

| Rotator Cuff | A group of four muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis) that stabilize the shoulder joint and allow for a wide range of shoulder movements. |

| Scapula | The shoulder blade, a triangular bone that connects with the humerus and clavicle. |

| Subdeltoid Bursa | A fluid-filled sac reducing friction between muscles and bones during shoulder movement. |

| Supraspinatus Muscle | A rotator cuff muscle situated on the upper portion of the scapula, initiating arm abduction. |

| Teres Major Muscle | A muscle that assists in the internal rotation and adduction of the arm, not part of the rotator cuff. |

| Teres Minor Muscle | The smallest of the rotator cuff muscles, contributing to the external rotation of the arm. |

| Tennis Elbow | Also known as lateral epicondylitis, a condition resulting from overuse or strain of the forearm extensor muscles, leading to pain and tenderness around the lateral epicondyle. |

| Transverse Humeral Ligament | A ligament that holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps in place. |

| Ulnar Nerve | A nerve running in a groove on the posterior side of the humerus, responsible for sensations in the fourth and fifth fingers and the inner half of the hand. When inflamed or compressed, it leads to Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. |