Table of Contents

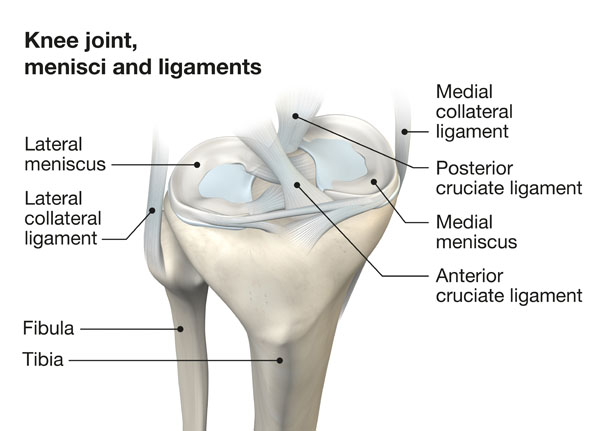

Anatomical Illustration of the Knee Joint

This image provides an anatomical illustration of the knee joint, highlighting the menisci and ligaments which are critical components for the knee’s function. The knee joint is a complex hinge joint that allows for flexion and extension, as well as a small degree of medial and lateral rotation.

Starting with the bones, we see the femur or thigh bone at the top, and below it are the tibia, the larger shin bone, and the fibula, the thinner bone located on the lateral side of the leg.

The menisci, shown here, are two crescent-shaped cartilages between the femur and tibia. The lateral meniscus is on the outer side of the knee and is more circular, while the medial meniscus, found on the inner side, is more C-shaped. These structures act as shock absorbers and provide stability to the knee by evenly distributing the body’s weight across the joint.

Surrounding the knee are the ligaments, which are tough bands of connective tissue that stabilize the joint. The medial collateral ligament runs along the inside of the knee and resists widening of the inside joint space. Conversely, the lateral collateral ligament is found on the outside of the knee and resists widening of the outer joint space.

Additionally, within the knee joint, there are the cruciate ligaments which cross each other to form an ‘X’. The anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, and the posterior cruciate ligament, or PCL, prevents the tibia from sliding backwards.

These components work together to allow movement and provide stability to the knee joint during activities like walking, running, and jumping. Damage or injury to any of these parts can significantly affect knee function and stability.

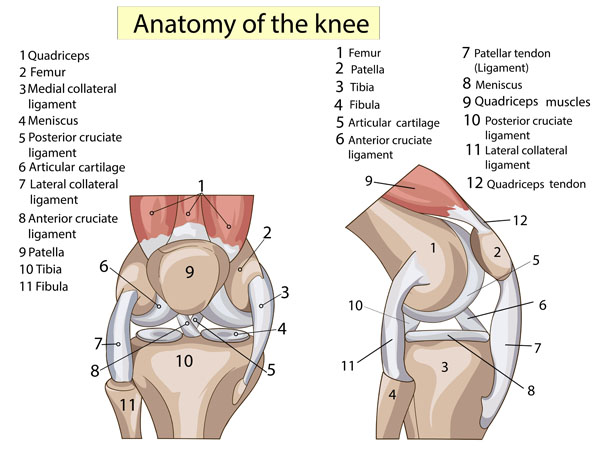

Detailed Anatomy of the Knee

This illustration provides a detailed view of the anatomy of the knee, displayed in two different angles for comprehensive understanding. The knee is one of the largest and most complex joints in the human body.

At the top of both views, the quadriceps muscle is indicated, which is a powerful group of muscles on the front of the thigh that are essential for knee extension and straightening the leg. Attached to the quadriceps is the patella, also known as the kneecap, which is a small bone that sits in front of the knee joint providing protection and increasing leverage for the quadriceps muscles.

Below the patella is the tibia, the main bone of the lower leg that bears weight, and the fibula, which is the slender bone running alongside the tibia. These bones form the lower part of the knee joint. The surfaces of the tibia and the femur, the thigh bone above, are covered by articular cartilage, a smooth substance that cushions the bones and enables them to move easily.

Between the femur and tibia lie the menisci, two pads of cartilaginous tissue that distribute weight and reduce friction during movement. The medial meniscus is located on the inside of the knee, and the lateral meniscus on the outside.

The knee’s stability is provided by several ligaments. The medial collateral ligament, situated on the inside of the knee, and the lateral collateral ligament, on the outside, control the sideways motion of the knee and brace it against unusual movement. The anterior cruciate ligament, found in the center of the knee, prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, while the posterior cruciate ligament, also in the center, prevents the tibia from sliding backward.

Finally, the patellar tendon, sometimes referred to as the patellar ligament, connects the patella to the tibia and the quadriceps tendon connects the quadriceps muscle to the patella. These tendons work together to enable the knee to extend during activities like kicking, running, and jumping. Understanding the anatomy of the knee is crucial for diagnosing and treating knee injuries, which are common in both athletes and the general population.

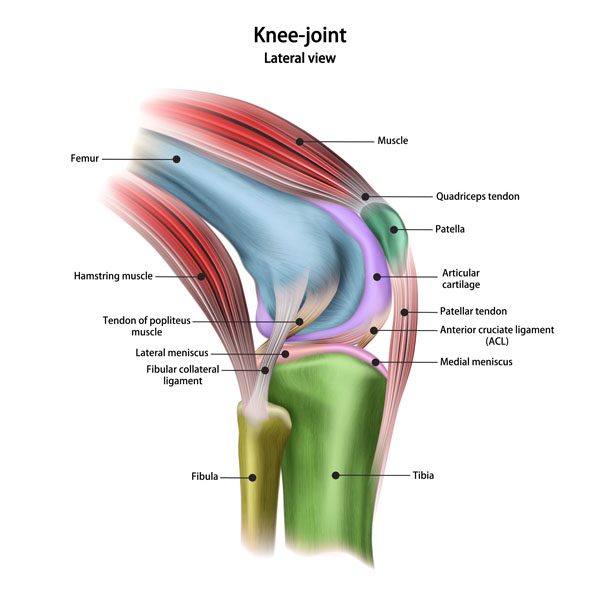

Knee Joint: Lateral View

This illustration presents a lateral view of the knee joint, which means we are looking at the joint from the side.

At the top, we see the femur, or thigh bone, which is the longest bone in the body. Covering the femur and extending down are the muscles of the thigh. The red-colored muscles represent the quadriceps group, which are the main extensors of the knee, critical for standing, walking, and running. The blue-colored muscles behind the femur represent the hamstrings, which are the primary flexors of the knee.

The quadriceps muscles converge into the quadriceps tendon, which is shown inserting on the patella, or kneecap. This tendon is essential for transmitting the force generated by the quadriceps to extend the knee. Below the patella is the patellar tendon, which connects the patella to the tibia, the shinbone. This tendon is vital for knee extension as well.

We can also see the articular cartilage, which is a smooth, slippery material that covers the ends of the femur and tibia, and the back of the patella. It reduces friction between the bones, allowing them to glide over each other during movement.

The illustration highlights the lateral meniscus and medial meniscus, two C-shaped pieces of cartilage that act as shock absorbers between the femur and tibia. They play a crucial role in stabilizing the knee and distributing weight across the joint.

The fibular collateral ligament is seen on the outside of the knee, connecting the femur to the fibula, the smaller bone of the lower leg. This ligament stabilizes the lateral aspect of the knee.

Just behind the patellar tendon is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which is one of the key ligaments that help stabilize the knee joint by preventing the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur.

Additionally, we see the tendon of the popliteus muscle, which is located at the back of the knee and helps to unlock the knee when transitioning from a standing to a walking position by rotating the tibia.

This complex network of bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and cartilage works in harmony to allow the knee to function correctly, making it capable of withstanding the heavy loads associated with activities like jumping and running, while also providing the fine control necessary for movements such as walking and squatting.

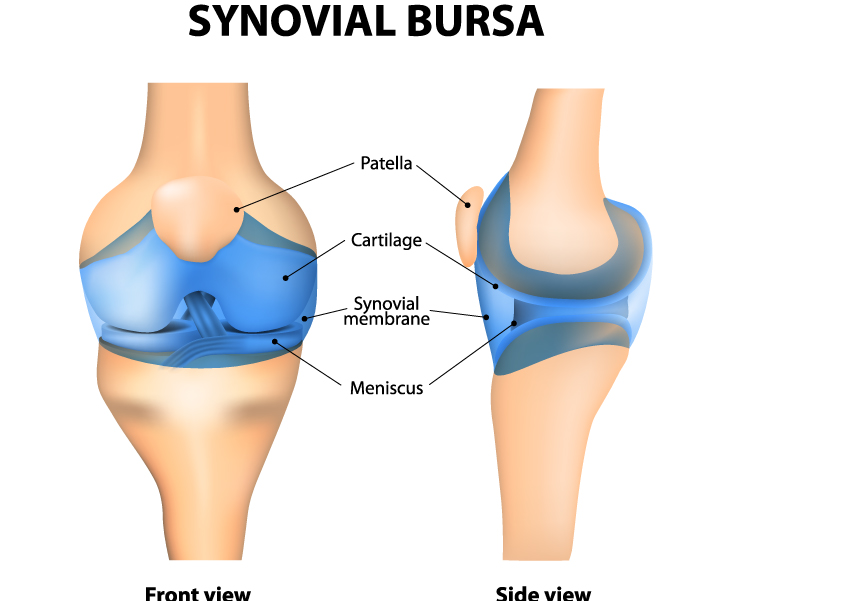

Synovial Bursa

This image presents a vivid depiction of a human knee joint, displaying both front and side views. It highlights the key components that facilitate the joint’s movement and stability.

In the front view, we see the patella, commonly known as the kneecap, which is a small bone that sits in front of the knee joint. It acts as a shield for the joint and increases the leverage of the thigh muscles that extend the leg.

Beneath the patella is the cartilage, a smooth, slippery tissue that covers the ends of bones in joints. Its primary function is to reduce friction during joint movement and help absorb shock.

We also see the synovial membrane, which lines the joint and secretes synovial fluid for lubrication. This fluid reduces friction between the cartilage-covered articulating surfaces, allowing for smooth movement within the joint.

The meniscus is a C-shaped piece of tough, rubbery cartilage that acts as a shock absorber between the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone). Menisci also improve the fit and stability of the joint.

In the side view, these structures are depicted from a different angle, offering a clear understanding of their three-dimensional placement within the knee. The depiction serves to enhance one’s comprehension of the complex anatomy and the interrelationship between the components of the knee joint.

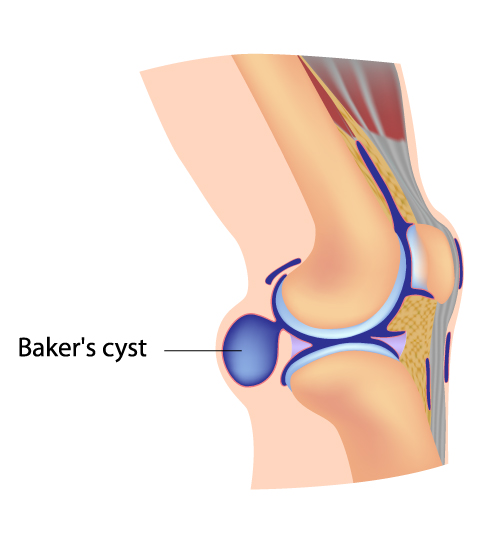

Baker's Cyst Pathology

This illustration depicts a Baker’s cyst, also known as a popliteal cyst, which is shown in the context of the knee joint from a side perspective. A Baker’s cyst is a fluid-filled sac that forms behind the knee. It is caused by the accumulation of synovial fluid, which can result from increased fluid production in the knee due to conditions like arthritis or meniscus tears.

The cyst is located in the popliteal area, which is the shallow depression located at the back of the knee joint. This fluid collection can lead to a sense of fullness or a bulge behind the knee, which may be accompanied by pain, particularly when extending or fully flexing the knee.

The image also shows the surrounding structures such as the muscles and tendons for context, but the focus is on the cyst itself. Treatment for a Baker’s cyst often involves addressing the underlying cause, and the cyst may resolve once the associated condition is treated. If the cyst is causing discomfort or complications, it may be managed with medication, physical therapy, or in some cases, surgical intervention.

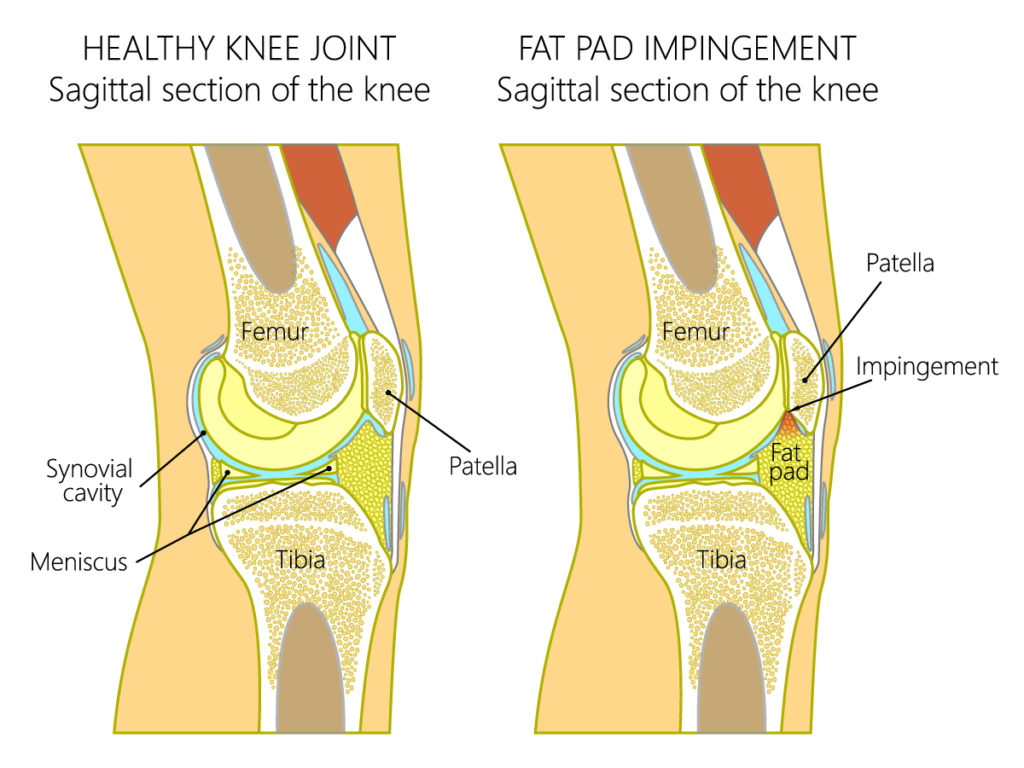

Fat Pad Impingement Pathology

This image depicts a side-by-side comparison between a healthy knee joint and one experiencing fat pad impingement, illustrated in sagittal sections, which are vertical cuts that divide the knee into left and right parts.

On the left, the healthy knee joint shows the proper anatomical structure. The femur, or thigh bone, sits above the tibia, the larger bone of the lower leg. The patella, or kneecap, is situated in front of the joint, providing structural support. Between the femur and tibia, we see the meniscus, a C-shaped piece of cartilage that cushions and stabilizes the joint. Surrounding the joint is the synovial cavity, which is filled with synovial fluid; this fluid reduces friction and allows for smooth movement of the joint.

On the right, we see a knee with fat pad impingement. The infrapatellar fat pad is an intracapsular but extrasynovial structure, meaning it is inside the joint capsule but outside the synovial membrane. It’s located below the patella, behind the patellar tendon. Fat pad impingement occurs when the fat pad becomes pinched between the femur and the tibia, often due to hyperextension or direct trauma. This can cause swelling and pain in the affected area, which is indicated by the area labeled ‘Impingement’.

In a healthy knee, the fat pad is not compressed; however, with impingement, the space in which the fat pad resides becomes compromised, leading to inflammation and discomfort. This condition can limit knee extension and make activities such as walking, running, or kneeling painful. Proper diagnosis and treatment are essential for alleviating pain and preventing further injury to the knee.

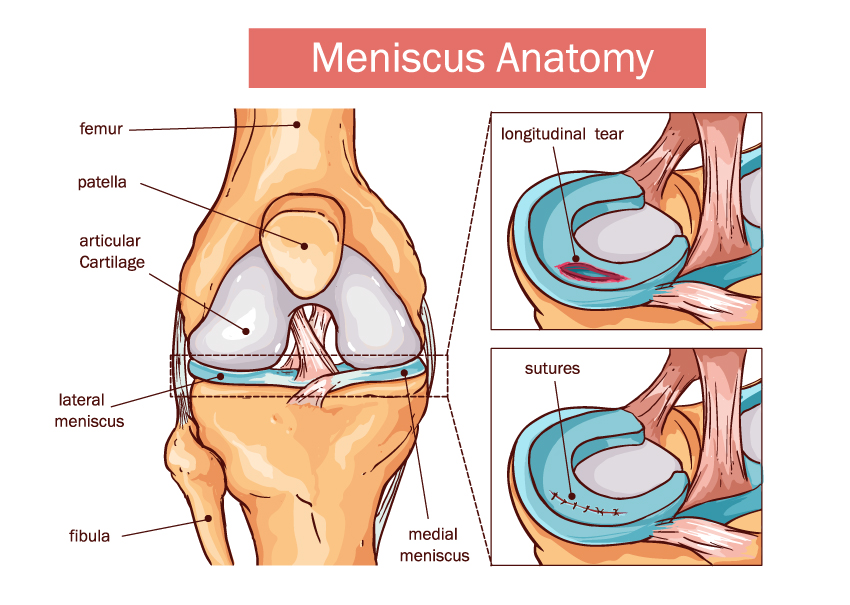

Meniscus Anatomy

The image shows a detailed view of the meniscus anatomy within the human knee. On the left, we see the knee joint in a frontal section, highlighting the major components that contribute to its structure and function. The femur, or thigh bone, forms the top part of the joint, articulating with the tibia, or shin bone, which is not labeled but is the larger bone directly under the femur. The patella, commonly known as the kneecap, is situated at the front of the knee joint and is connected to the quadriceps muscles by the quadriceps tendon and to the tibia by the patellar tendon. Articular cartilage is a smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of the bones where they come into contact with each other, facilitating smooth movement within the joint.

Two types of menisci, the medial and lateral, are shown as crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures between the femur and tibia. The lateral meniscus is on the outer part of the knee, and the medial meniscus is on the inner part. These structures act as shock absorbers and stabilize the joint.

On the right, we have close-up views of the meniscus exhibiting two conditions. The upper image depicts a longitudinal tear, a common type of meniscus injury characterized by a tear along the length of the meniscus. Below, we see a depiction of sutures used to repair a meniscal tear, indicating a surgical approach to treating such injuries.

This image could serve as an educational tool to explain the anatomy of the knee, the importance of the menisci in knee stability and motion, as well as the nature of meniscal injuries and their surgical management.

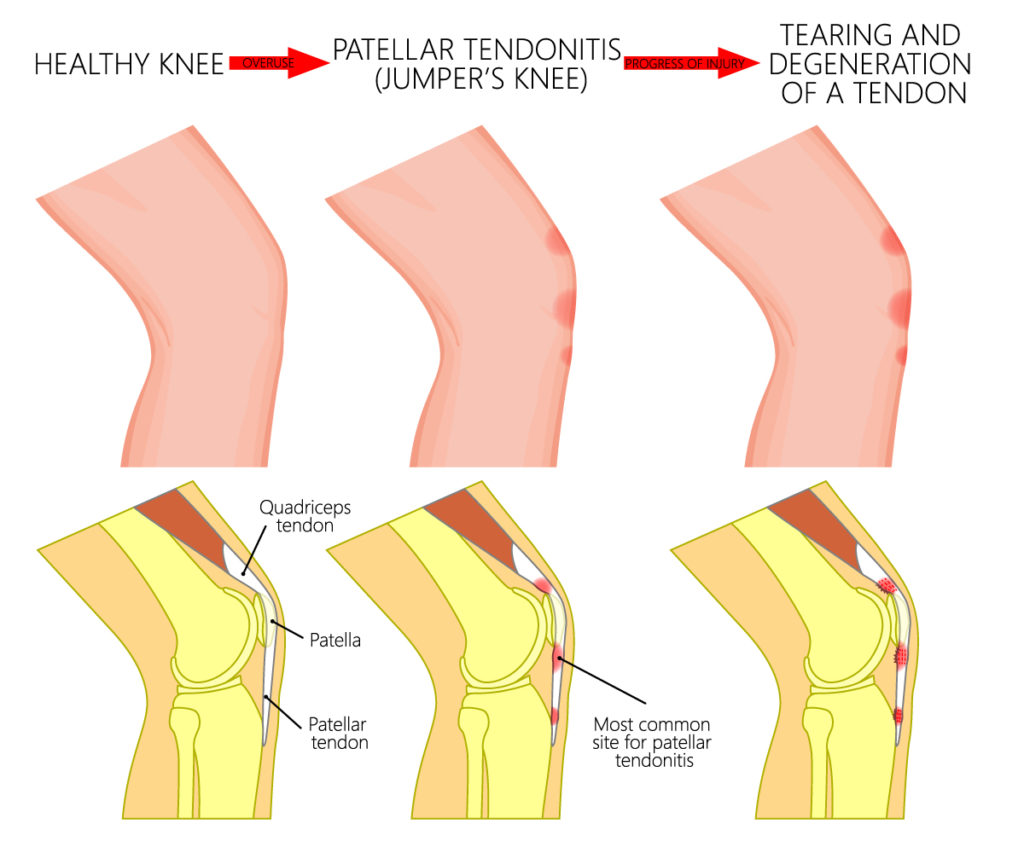

Tendon Pathology

The image provides a comparative view of a healthy knee versus knees with pathological conditions, specifically focusing on the patellar tendon.

The top row shows three stages of the tendon’s condition. The first, labeled “HEALTHY KNEE,” depicts a normal, unaffected tendon with a smooth, uninterrupted appearance. The middle image is labeled “PATELLAR TENDONITIS (JUMPER’S KNEE),” where the tendon shows a slight irregularity, representing inflammation or microtears commonly seen in athletes who engage in jumping sports. The final image on the top row, “TEARING AND DEGENERATION OF A TENDON,” illustrates a more severe condition with visible damage and degeneration, indicating chronic tendinopathy or possible partial tears.

The bottom row provides a closer anatomical view of the knee, detailing the relationship between the patella, patellar tendon, and quadriceps tendon. The leftmost image shows a healthy knee where the patellar tendon, which connects the patella to the tibia, and the quadriceps tendon, which connects the quadriceps muscle to the patella, are intact and without damage. The middle image highlights the “Most common site for patellar tendonitis” just below the patella, where repetitive stress or acute injury can cause pain and swelling. The rightmost image in the bottom row likely corresponds to the “TEARING AND DEGENERATION” stage, showing significant changes at the same site, which suggest chronic injury and deteriorated tendon integrity.

This visual representation serves to educate about the progression of patellar tendon conditions, from a healthy state through to inflammation and degeneration, emphasizing the importance of recognizing and addressing early symptoms to prevent long-term damage.

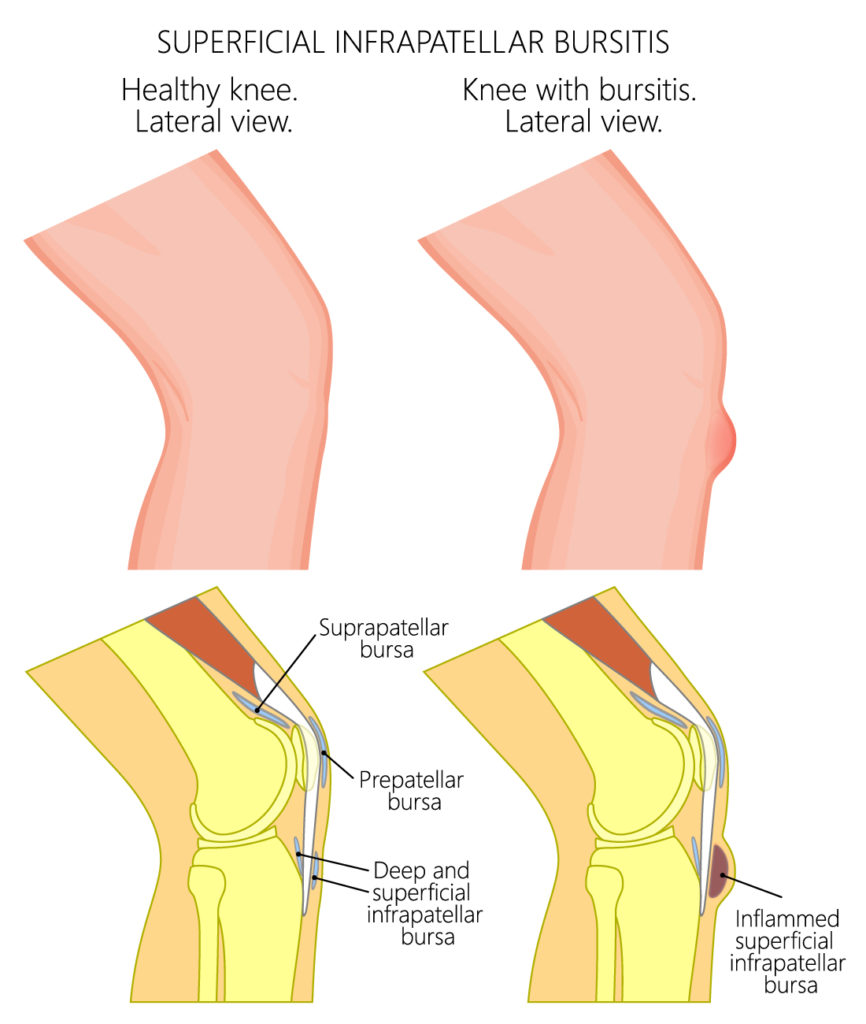

Infrapatellar Bursitis

This image contrasts the lateral view of a healthy knee with a knee suffering from superficial infrapatellar bursitis.

In the healthy knee, we see a lateral view of the knee joint, which does not show any signs of inflammation or swelling. The key structures labeled are the suprapatellar bursa, located above the patella, and the prepatellar bursa, situated in front of the patella. Also labeled are the deep and superficial infrapatellar bursae, which are located below the patella. Bursae are small fluid-filled sacs that act as cushions to reduce friction between the bones and the tendons or skin.

On the right side, the image illustrates a knee afflicted with bursitis, specifically in the superficial infrapatellar bursa. This condition is highlighted by the presence of inflammation in the bursa, which is located just below the patella and above the tibial tuberosity. Bursitis can cause pain and swelling and is often a result of overuse, repetitive motion, or direct trauma to the knee.

This kind of visual aid is valuable for educational purposes, providing clear insight into the anatomy of the knee and the changes that occur during inflammatory conditions like bursitis. Treatment for bursitis typically includes rest, ice, compression, and elevation (R.I.C.E), along with anti-inflammatory medications to alleviate pain and reduce swelling.

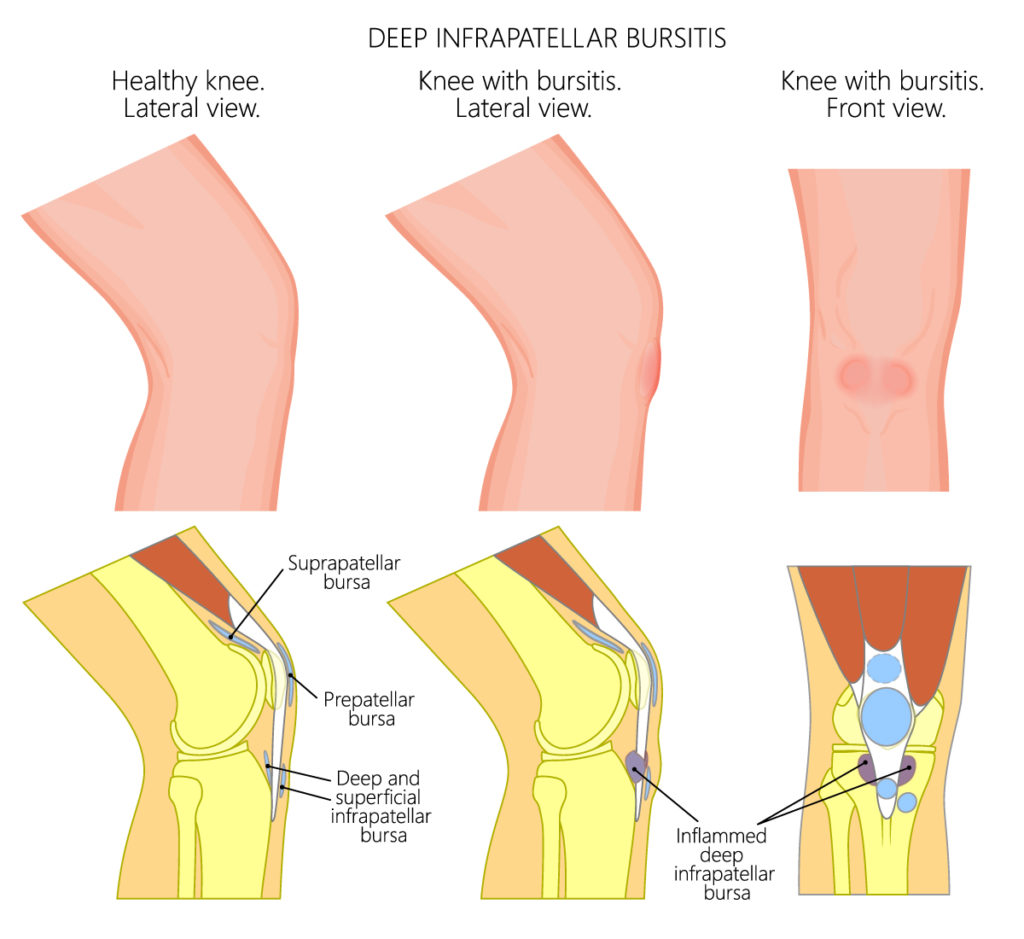

Deep Infrapatellar Bursitis

The diagram depicts a comparison between a healthy knee and knees affected by deep infrapatellar bursitis from both lateral and front views.

On the left side of the diagram, we see the healthy knee’s lateral view. It shows the normal anatomy without any signs of inflammation, identifying the suprapatellar bursa, prepatellar bursa, and the deep and superficial infrapatellar bursae. These bursae are small, fluid-filled sacs that help reduce friction and cushion pressure points between the bones and the tendons or muscles around the knee joint.

The middle image presents a lateral view of a knee with deep infrapatellar bursitis. This condition is indicated by the inflammation of the deep infrapatellar bursa, which is situated below the patella (kneecap) and behind the patellar tendon. The inflammation is marked by a red area, suggesting swelling and irritation in the bursa.

On the right side, the diagram provides a front view of a knee with bursitis, highlighting the general area of swelling on the front of the knee, which corresponds with the location of the inflamed deep infrapatellar bursa seen in the middle image.

Deep infrapatellar bursitis is often associated with individuals who frequently engage in kneeling, leading to irritation and inflammation of the bursa located beneath the patellar tendon. Symptoms typically include pain and swelling in the affected area, and the condition is managed with treatments such as rest, ice, compression, elevation, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

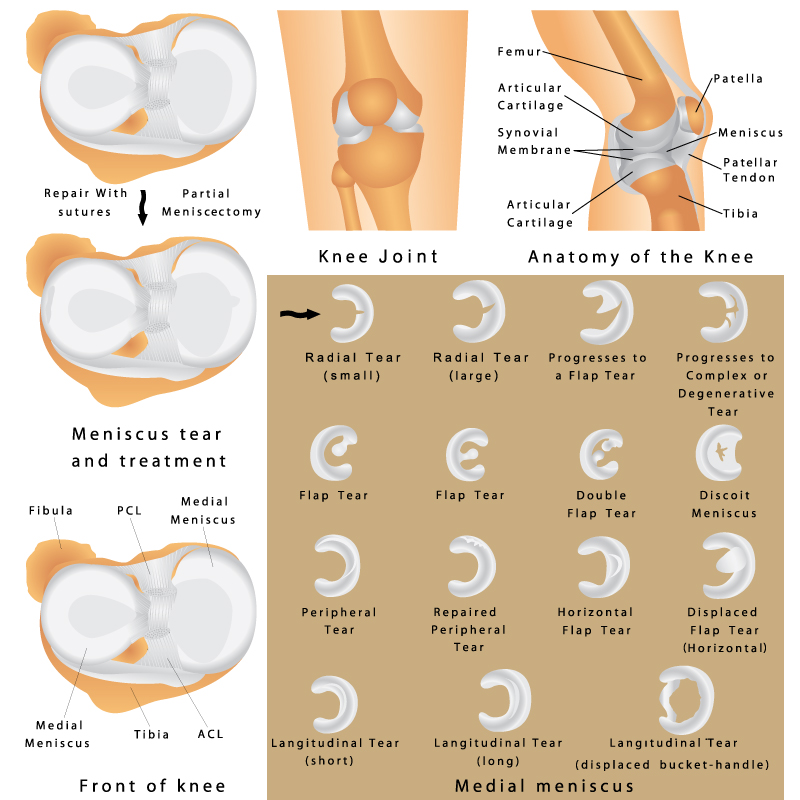

Meniscus Tear Pathology

This comprehensive image offers an overview of the knee joint’s anatomy, the various types of meniscus tears, and their respective treatments.

In the upper right quadrant, the image displays a simplified lateral view of the knee, identifying key structures such as the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), patella (kneecap), meniscus, patellar tendon, articular cartilage, and the synovial membrane. This anatomical layout is essential for understanding knee function and the context for potential injuries.

The central part of the image illustrates the progression of a meniscus tear. Starting with a small radial tear, it can enlarge to a larger radial tear, and with further degeneration, it can develop into a flap tear. The illustration continues to show that a flap tear can progress further into a complex or degenerative tear, highlighting the potential worsening of an untreated meniscus injury.

On the bottom left, the focus shifts to meniscus tear treatment options. At the very bottom, there is an image of the medial meniscus with an adjacent description, “Repair with sutures,” suggesting this is a treatment method for certain types of meniscus tears. Just above, there’s an image labeled “Partial Meniscectomy,” indicating another treatment approach where part of the meniscus is surgically removed.

The left side of the image breaks down various types of meniscal tears in detail. Each tear is depicted on a silhouette of the medial meniscus, providing a clear visualization of the tear’s location and shape. The types of tears shown include:

- Radial tear, both small and large, located at the inner edge of the meniscus.

- Flap tear, where a portion of the meniscus is displaced, creating a “flap.”

- Double flap tear, indicating two separate “flap” formations.

- Discoid meniscus, an anomaly where the meniscus is thicker and more disc-like than usual.

- Peripheral tear, along the outer edge of the meniscus.

- Repaired peripheral tear, showing the result of surgical repair.

- Horizontal flap tear, where the tear runs horizontally across the meniscus.

- Displaced flap tear (horizontal), where a horizontally torn flap is moved from its original position.

- Longitudinal tear, depicted in short and long versions, running along the length of the meniscus.

- Longitudinal tear (displaced bucket-handle), which shows a severe form where the inner part of the tear displaces into the joint, resembling a bucket handle.

The images in this file are designed to educate about the intricate details of knee anatomy and the complexity of meniscus injuries, serving as a valuable resource for medical students, healthcare professionals, and patients seeking to understand meniscal pathology and the corresponding treatment options.

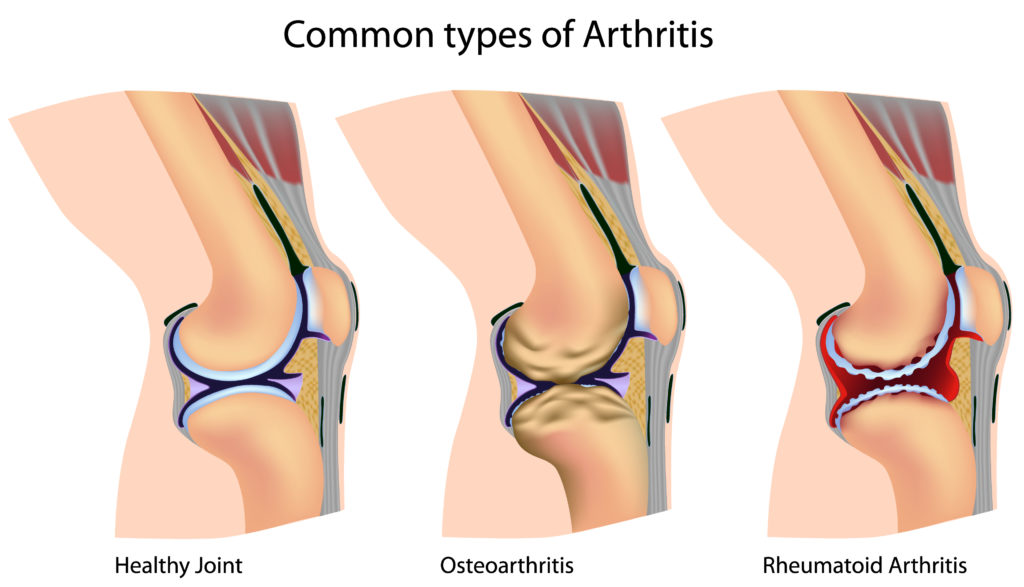

Knee Arthritis Pathology

This image presents a comparative view of a healthy knee joint alongside two common types of arthritis: osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

In the first illustration labeled “Healthy Joint,” the knee is shown with intact articular cartilage, which is the smooth, white tissue covering the ends of bones where they come into contact with each other to form a joint. The blue structure depicted is the synovial membrane, which releases synovial fluid acting as a lubricant to minimize the friction between the articular cartilages during movement. The meniscus, a type of cartilage that acts as a shock absorber and aids in load distribution within the joint, appears undamaged.

The second image illustrates “Osteoarthritis,” characterized by the breakdown of joint cartilage and the underlying bone. Noticeable in this depiction is the roughening and reduction in cartilage thickness, changes in the bone structure including bone spurs or osteophytes, and a decrease in the joint space due to cartilage loss. These changes can lead to pain, swelling, and reduced motion in the joint.

The third image portrays “Rheumatoid Arthritis,” an autoimmune condition that leads to inflammation of the synovial membrane, causing it to thicken and invade the surrounding joint tissues. The illustration shows the inflamed synovial membrane with an excessive production of synovial fluid, leading to swelling. There is also the presence of pannus formation, which is a thickened layer of synovial tissue that destructively covers the articular cartilage and can lead to cartilage erosion and joint deformity.

The representation of these conditions side by side allows for a clear understanding of the anatomical changes that occur in arthritis, which is critical for medical education and patient awareness. Each type of arthritis has different treatments ranging from lifestyle modifications and medications to surgical interventions, depending on the severity and progression of the disease.

Patellar Tendon Injuries

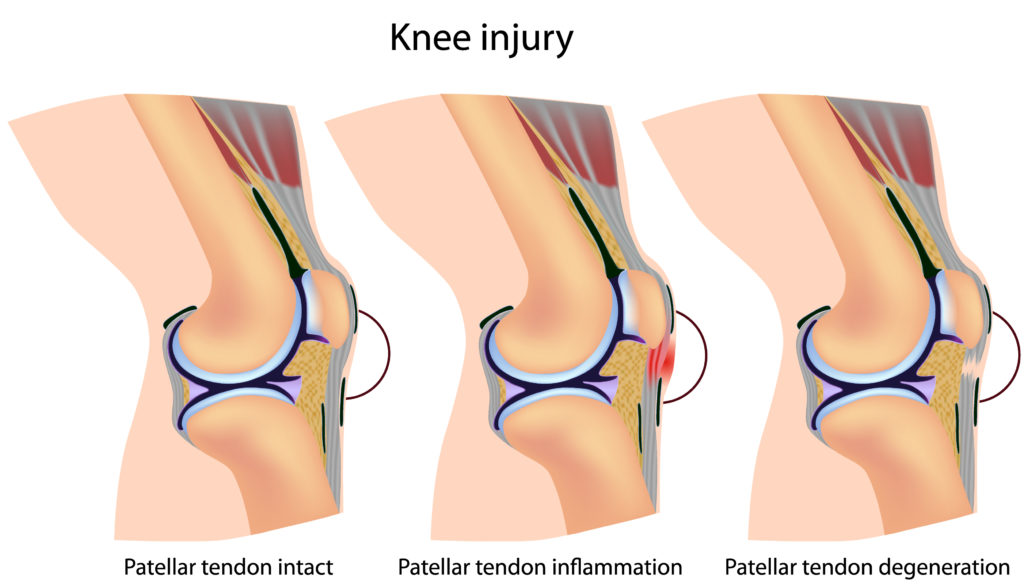

This image provides a comparative view of a healthy knee and stages of patellar tendon injury.

On the left, the illustration shows a normal, healthy knee with an intact patellar tendon, which is the structure connecting the patella (kneecap) to the tibia (shinbone). This tendon is crucial for knee extension, which is necessary for activities like walking, running, and jumping.

The middle image illustrates a knee with patellar tendon inflammation, a condition known as patellar tendinitis or jumper’s knee. This is often a result of overuse, particularly in sports that involve frequent jumping and running. The inflamed tendon is indicated by the red shading surrounding it.

The image on the right shows a knee with patellar tendon degeneration. This condition represents a more advanced stage of tendon damage, where the structure of the tendon is compromised, leading to weakening and potential tears. Degeneration is often the result of chronic overuse and insufficient healing time, leading to a breakdown of the tendon tissue.

Understanding the progression of patellar tendon injuries is vital for both prevention and treatment. Early stages may be managed with rest, ice, and physical therapy, while more advanced degeneration might require a longer period of rehabilitation or even surgical intervention.

Anatomical Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) | A key ligament within the knee joint that prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur. |

| Articular Cartilage | Smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones in joints, facilitating smooth movement and reducing friction. |

| Baker's Cyst (Popliteal Cyst) | A fluid-filled sac behind the knee, caused by the accumulation of synovial fluid, leading to swelling and discomfort. |

| Bursitis | Inflammation of a bursa, causing pain and swelling in the affected area, often due to overuse, stress, or injury. |

| Deep Infrapatellar Bursitis | Inflammation of the bursa located below the patella and behind the patellar tendon, causing pain and swelling. |

| Femur | The thigh bone, which is the longest bone in the body and forms the top part of the knee joint. |

| Fibula | The thinner bone located on the lateral side of the leg, contributing to the stability of the ankle and supporting lower leg muscles. |

| Lateral Collateral Ligament | Found on the outside of the knee, it resists widening of the outer joint space. |

| Lateral Meniscus | The more circular cartilage on the outer side of the knee, acting as a shock absorber and providing stability. |

| Medial Collateral Ligament | Runs along the inside of the knee and resists widening of the inside joint space. |

| Medial Meniscus | The more C-shaped cartilage on the inner side of the knee, serving as a shock absorber and stabilizer. |

| Menisci | Two crescent-shaped cartilages between the femur and tibia that act as shock absorbers and provide stability to the knee. |

| Osteoarthritis | Characterized by the breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone, leading to pain, swelling, and reduced motion. |

| Patella (Kneecap) | A small bone in front of the knee joint that protects it and increases the leverage of the quadriceps muscles. |

| Patellar Tendon | Connects the patella to the tibia and is vital for knee extension. |

| Patellar Tendonitis (Jumper’s Knee) | Inflammation or microtears in the patellar tendon, often resulting from overuse in sports. |

| Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) | Prevents the tibia from sliding backwards under the femur. |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | An autoimmune condition causing inflammation of the synovial membrane, leading to swollen, painful joints and potential deformity. |

| Synovial Bursae | Small fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction between moving tissues in the knee joint. |

| Tibia | The shin bone, which is the larger bone of the lower leg and bears most of the body’s weight. |