1914 Torso Front Anatomy

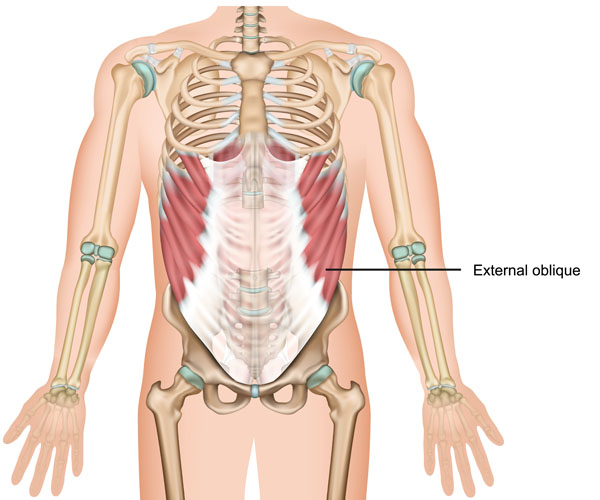

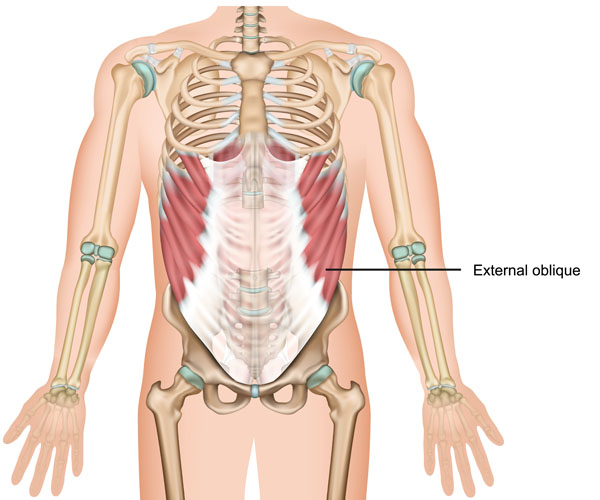

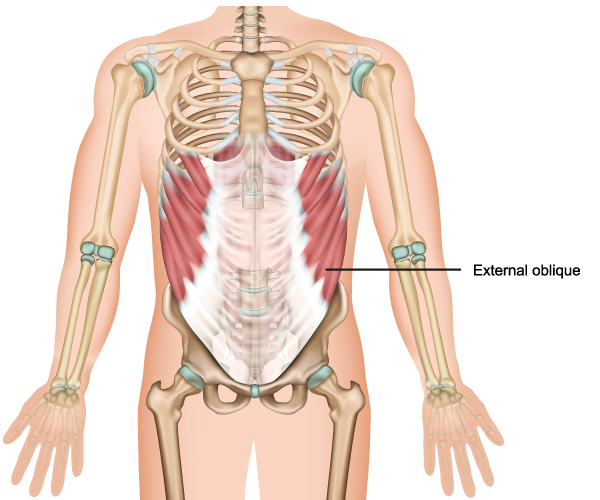

The illustration showcases the human torso from the posterior view, with a focus on the superficial muscles and skeletal framework. Central to the image is the vertebral column, which provides structural support and houses the spinal cord. The ribs, articulated with the thoracic vertebrae, create the thoracic cage that protects vital organs such as the heart and lungs.

Prominently featured in the image are the external oblique muscles, which are part of the abdominal musculature. These muscles are located on the lateral and anterior parts of the abdomen on each side. Their muscle fibers run diagonally downward and medially, from the lower ribs to the pelvis. The external obliques function in the movement and support of the trunk, assisting in actions such as twisting the waist and bending the torso sideways. They also play a role in compressing the abdominal cavity, thus supporting the abdominal viscera and contributing to processes like forced expiration.

The illustration also hints at the lower extremities initiating at the pelvis, although they are not the focus of this image. The skeletal structure of the pelvis is partially visible, which connects the spine to the lower limbs and supports the gastrointestinal and urogenital organs.

In this posterior view, the scapulae or shoulder blades are also visible, articulating with the humerus of the upper limbs at the glenohumeral joint. This joint allows for a wide range of upper limb movements. The hands are extended outwards, showcasing the distal ends of the forearm bones – the radius and ulna.

Overall, the image serves as an educational tool to understand the superficial musculoskeletal anatomy of the human torso and upper limbs.

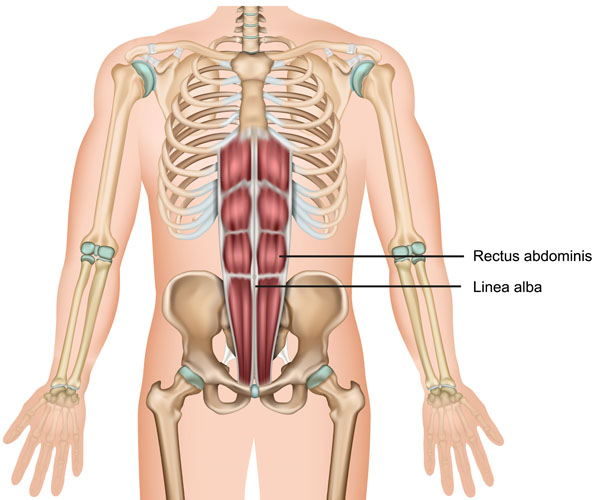

This image provides a posterior view of the human torso, highlighting the rectus abdominis muscles and the linea alba. The rectus abdominis is a paired muscle running vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the human abdomen. The muscles are separated by a narrow band of connective tissue called the linea alba, which extends from the xiphoid process of the sternum to the pubic symphysis.

The rectus abdominis muscles are commonly known as the “abs” and are important for maintaining posture and protecting the internal organs; they also play a key role in movements such as flexing the spine. The segmented appearance of the rectus abdominis is due to three or more horizontal tendinous intersections called tendinous inscriptions. These inscriptions give the muscle a distinctive “six-pack” appearance in individuals with low body fat.

The linea alba, seen in the midline, is a fibrous structure that forms the seam of the two rectus muscles and provides an attachment point for other abdominal muscles. It’s a critical landmark in surgeries and a point of weakness where hernias can occur.

Also depicted are the thoracic cage composed of ribs and the thoracic vertebrae, and the pelvic girdle at the base. The upper limbs are presented with the arms placed laterally, showing the scapula, humerus, and the bones of the forearm – the radius and ulna – leading to the hands. The image doesn’t focus on these structures but provides context to the location of the rectus abdominis and linea alba within the human body.

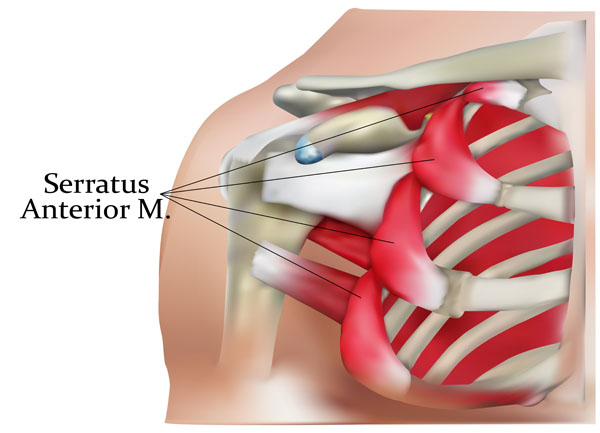

This image illustrates a detailed view of the serratus anterior muscle, a key structure in the lateral part of the thorax. The serratus anterior is a fan-shaped muscle that originates from the first to the eighth or ninth ribs at the side of the chest and inserts along the entire anterior length of the medial border of the scapula.

The muscle is named for its serrated appearance, resembling a saw’s teeth, with individual slips or ‘fingers’ extending from the ribs to the scapula. These digitations can be clearly seen in the image, which show the muscle’s path over the rib cage.

The serratus anterior plays a pivotal role in the movement of the scapula, contributing to the protraction and upward rotation of the shoulder blade, which is essential for raising the arm above the head. It also helps to hold the scapula against the thoracic wall.

Clinically, the integrity of the serratus anterior is important for shoulder stability and function. Weakness or paralysis of this muscle can lead to a condition known as ‘winged scapula’, where the medial border of the scapula protrudes backward, resembling a wing.

The image provides a clear view of how the serratus anterior is positioned relative to the ribs and the scapula, highlighting its importance in the musculoskeletal and functional anatomy of the shoulder girdle.

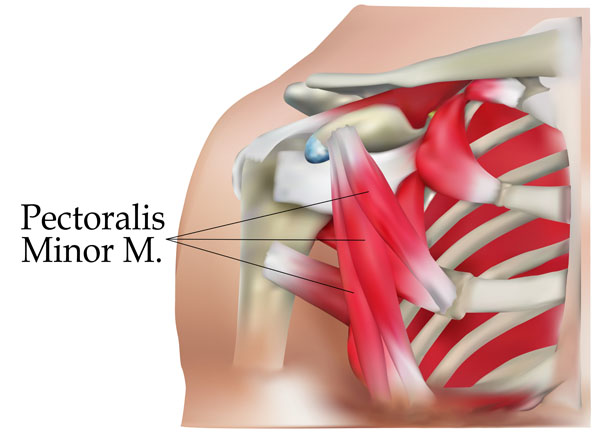

This illustration provides a detailed view of the pectoralis minor muscle, a significant muscle within the chest of the human body. The pectoralis minor is a thin, triangular muscle, situated beneath the pectoralis major—the larger and more superficial chest muscle. It originates from the third, fourth, and fifth ribs and extends diagonally upward to insert at the coracoid process of the scapula.

The pectoralis minor is involved in several movements of the scapula, including the downward rotation, depression, and protraction of the scapula. It plays a crucial role in stabilizing the scapula by drawing it anteriorly and inferiorly against the thoracic wall. This action is vital for movements such as reaching or pushing with the upper limb.

The anatomical context of the image highlights the muscle’s positioning in relation to the ribcage and the scapula, showcasing its attachment points which are key to its function. The visibility of the ribs and the partial view of the scapula help in understanding the location and the potential movements facilitated by the pectoralis minor muscle. Understanding the anatomy and function of the pectoralis minor is important for comprehending the mechanics of the shoulder girdle and upper limb movement.

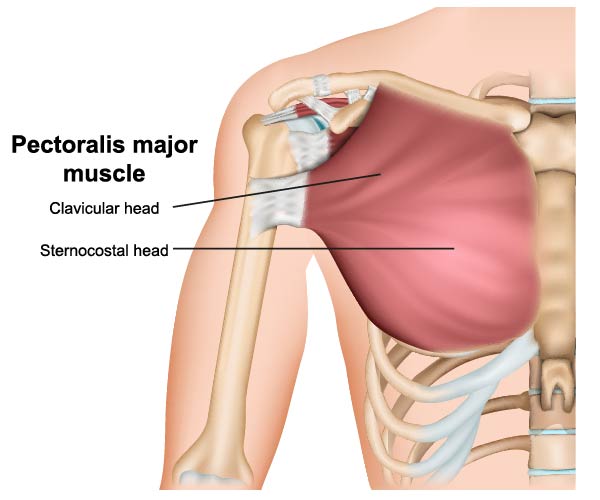

The image provides an anatomical illustration of the pectoralis major muscle, a prominent muscle of the upper chest. The pectoralis major has two distinct heads:

Clavicular Head: This portion of the muscle originates from the medial half of the clavicle. It’s responsible for flexing the humerus, as in the action of bringing the arm toward the front of the body from a relaxed side position.

Sternocostal Head: The larger and more substantial part of the muscle, the sternocostal head, has its origins from the sternum, the cartilage of the first six ribs, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. This part of the pectoralis major contributes to several movements, including the adduction of the humerus, drawing the arm toward the body’s midline, and medially rotating the humerus.

The entire pectoralis major muscle inserts into the bicipital groove of the humerus and functions chiefly in the movements of the shoulder joint. It plays a critical role in the movement of the shoulder girdle, including actions such as pushing, throwing, and climbing.

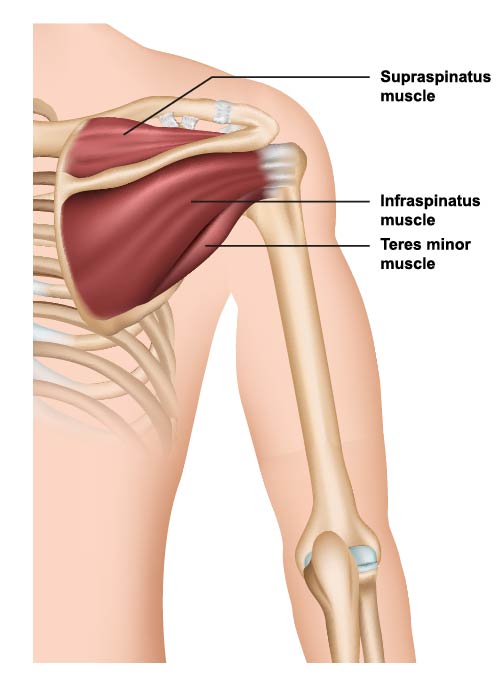

This image depicts a lateral view of the shoulder girdle, highlighting three of the four rotator cuff muscles, which are key to shoulder stability and movement:

Supraspinatus Muscle: Situated at the top of the shoulder, lying above the spine of the scapula, this muscle is responsible for the initial 15 degrees of arm abduction. It stabilizes the shoulder joint and helps lift the arm away from the body.

Infraspinatus Muscle: Located just below the supraspinatus, covering the infraspinous fossa of the scapula, the infraspinatus muscle is primarily involved in the external rotation of the shoulder joint. It also helps stabilize the shoulder by holding the head of the humerus in place.

Teres Minor Muscle: This small muscle is positioned just below the infraspinatus. It works in concert with the infraspinatus to externally rotate the shoulder joint and add to the overall stability of the shoulder.

These muscles are all part of the rotator cuff, a group of muscles and tendons that surround the shoulder joint, keeping the head of the upper arm bone firmly within the shallow socket of the shoulder. A healthy and strong rotator cuff ensures a wide range of motion of the arm and contributes to the fine motor movements necessary for activities like throwing or reaching overhead.

This illustration presents a posterior view of the human upper body, focusing on the muscular and skeletal anatomy. The central skeletal structure is the vertebral column, which extends from the base of the skull to the pelvis and serves as the main structural support of the body. The rib cage is also visible, attached to the thoracic vertebrae and encasing vital organs for protection.

The muscular structure labeled here is the external oblique. These are a pair of broad, thin, superficial muscles that lie on the lateral and anterior parts of the abdomen. Their fibers run diagonally from the lower ribs to the iliac crest of the pelvis, forming a V-shape. The external obliques are responsible for various movements of the trunk, including flexing the spine, twisting the waist, and compressing the abdominal wall. They play a significant role in movements such as bending sideways and rotating the trunk, as well as in forced expiration during breathing.

The image does not highlight other important structures such as the internal obliques, the transversus abdominis, or the rectus abdominis, which together with the external obliques form the abdominal wall. However, understanding the location and function of the external oblique is crucial in comprehending the complex mechanics of the human torso.

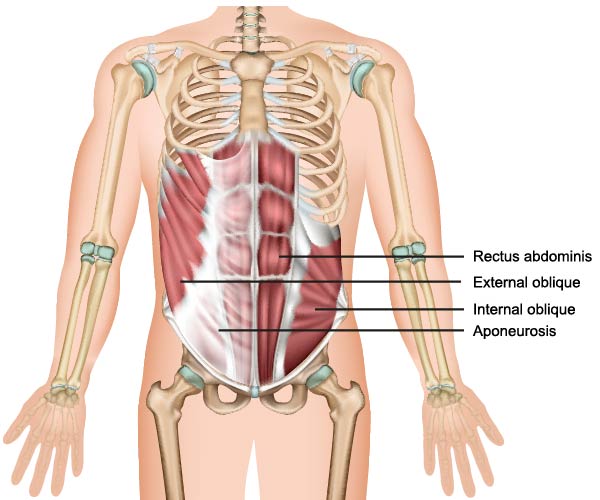

The image depicts a posterior view of the human torso, focusing on the muscular anatomy of the abdominal region. The muscles highlighted are the rectus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles, along with the aponeurosis.

The rectus abdominis muscle is a long, flat muscle extending along the length of the front of the abdomen. It is segmented by three fibrous bands called tendinous intersections, giving it a “six-pack” appearance in well-defined individuals. The muscle is responsible for flexing the lumbar spine, compressing the abdominal cavity, and stabilizing the pelvis during movement.

Lateral to the rectus abdominis are the external oblique muscles, which are part of the lateral abdominal muscles. Their fibers run diagonally down and medially, contributing to the twisting of the trunk and bending the torso to the side. These muscles also play a role in compressing the abdominal cavity.

Deep to the external obliques are the internal oblique muscles, whose fibers run perpendicular to those of the external obliques. They work synergistically with the external obliques for trunk rotation and lateral flexion, and also help in compressing the abdominal contents.

The aponeurosis, shown as a white sheath in the image, is a fibrous sheet that connects the abdominal muscles to the linea alba, a vertical line running down the midline of the abdomen. This structure is crucial for muscle attachment and force transmission across the abdominal wall.

Together, these muscles form the abdominal wall, which supports the trunk, holds the abdominal organs in place, and assists in movements such as bending and twisting.

This image depicts the posterior view of the human torso, specifically highlighting the external oblique muscles. These muscles are part of the lateral abdominal muscles and are situated on each side of the trunk. They extend from the lower ribs to the iliac crest of the pelvic bones, covering the sides of the abdominal region. The fibers of the external oblique muscles run downward and medially, like the hands in the pockets, and are responsible for various movements of the trunk, including trunk rotation and lateral flexion.

The muscles also play a crucial role in the movement and support of the trunk and contribute to the abdominal press, which increases the intra-abdominal pressure required for functions such as defecation, urination, childbirth, and forced expiration. Additionally, the external obliques assist with the stabilization of the core during movements and help to protect and contain the internal organs.

The skeletal structure visible in the image includes the vertebral column, which supports the upper body and houses the spinal cord. The ribs form a protective cage around the thoracic organs, and the pelvis serves as the foundation to which the lower limbs are attached. The humerus bones of the upper limbs can be seen articulating with the scapulae at the shoulder joints. The positioning of the hands and arms indicates the natural resting position of the upper limbs with respect to the torso.

Overall, the image serves as a useful visual guide for understanding the anatomy and function of the external oblique muscles within the context of the human musculoskeletal system.

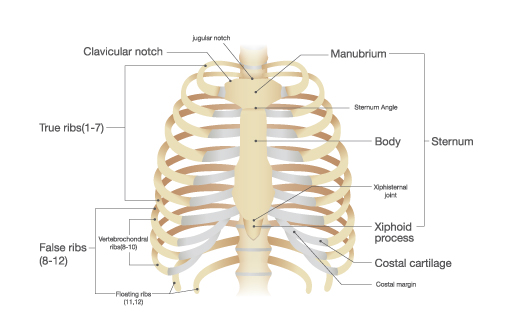

This illustration presents the components of the thoracic cage and sternum from an anterior perspective.

At the top, we see the jugular notch, a central indentation at the superior end of the sternum. Lateral to it on both sides are the clavicular notches, where the sternum articulates with the clavicles, or collarbones.

The sternum itself is divided into three regions:

- Manubrium: The broad, upper part, located centrally just below the jugular notch.

- Body: The longest part of the sternum, it connects to the manubrium at a location known as the sternal angle, which is an important clinical landmark for rib identification.

- Xiphoid Process: The small, cartilaginous projection at the lower end of the sternum, which becomes ossified in adults.

The thoracic cage is comprised of the ribs, which are categorized into three groups:

- True Ribs (1–7): These ribs attach directly to the sternum via their costal cartilages.

- False Ribs (8–12): Ribs that do not directly articulate with the sternum. Ribs 8 through 10 connect to the costal cartilage of the rib above, while ribs 11 and 12, also known as floating ribs, do not connect to the sternum at all.

- Floating Ribs (11, 12): These are the last two false ribs that have no anterior attachment to the sternum or other ribs.

The costal cartilages are shown connecting the ribs to the sternum, providing elasticity and allowing the rib cage to expand during respiration. The costal margin, the lower boundary of the thoracic cage, is also indicated.

This arrangement of bones and cartilage provides protection to the thoracic organs, including the heart and lungs, and serves as an attachment site for various muscles involved in respiration, movement of the upper limbs, and maintaining the position of the vertebral column.

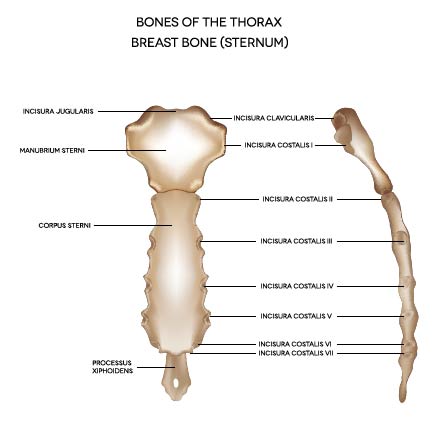

The image displays an anatomical representation of the sternum, also known as the breastbone, situated in the center of the thorax (chest). The sternum is a flat bone that forms the anterior part of the rib cage, serving as an attachment point for several ribs and muscles of the chest.

The sternum is composed of three main parts:

Manubrium Sternum: This is the uppermost section of the sternum, and it articulates with the clavicles (collarbones) at the clavicular notches and the first pair of ribs. The jugular notch is at the top of the manubrium and can be felt at the base of the neck between the collarbones.

Corpus Sterni (Body of Sternum): The longest part of the sternum, the body articulates with the manubrium at the sternal angle, which is palpable and important as a surface landmark for the second rib and the division between the superior and inferior mediastinum in the thoracic cavity. The body also has lateral borders where the costal cartilages of the ribs attach, specifically indicated by the incisurae costales (notches for the costal cartilages) from the second to the seventh rib.

Processus Xiphoideus (Xiphoid Process): The smallest and most variable part, the xiphoid process is the lower tip of the sternum. It is a thin, elongated projection that provides an attachment for the diaphragm, the main muscle of respiration, as well as the rectus abdominis and other abdominal muscles.

The sternum plays a crucial role in protecting vital organs in the thoracic cavity, including the heart and lungs, and provides structural support for the rib cage. The anatomical landmarks of the sternum are significant in clinical practice for procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), where the compressions are given on the lower half of the sternum, avoiding the xiphoid process to prevent injury.

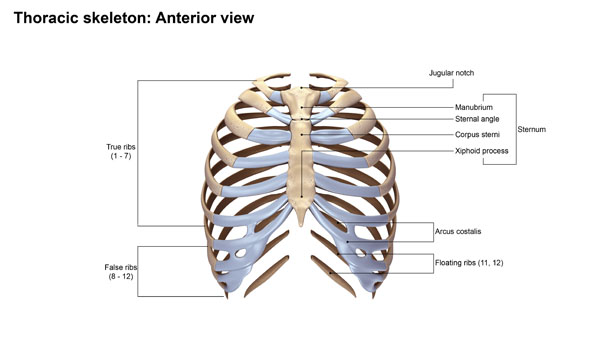

The image displays the thoracic skeleton from an anterior view, detailing the components of the thoracic cage and the sternum. Let’s break down the labeled parts:

Jugular Notch: This is the concave upper border of the sternum, visible as a depression at the level of the third thoracic vertebra, and is palpable at the superior end of the sternum between the clavicles.

Manubrium: The upper part of the sternum, a quadrangular bone that articulates with the clavicles and the first pair of ribs.

Sternal Angle: Also known as the “angle of Louis,” it is a palpable bony ridge between the manubrium and the body of the sternum. It is in line with the second rib and the intervertebral disc between T4 and T5.

Corpus Sterni (Body of Sternum): The longest part of the sternum; it articulates with the manubrium above and the xiphoid process below. It also provides attachment points for ribs two through seven.

Xiphoid Process: The smallest and most variable part of the sternum, it’s a thin, elongated cartilaginous process that ossifies in the adult.

True Ribs (1-7): These ribs attach directly to the sternum via their costal cartilage.

False Ribs (8-12): The ribs that do not directly articulate with the sternum. Ribs eight, nine, and ten are connected to the sternum through the cartilage of rib seven, while ribs eleven and twelve are floating ribs, with no anterior attachment to the sternum.

Floating Ribs (11, 12): These are the two lowermost false ribs that do not connect to the sternum or to the other ribs’ cartilage. They end in the posterior abdominal wall.

This thoracic skeleton structure provides protection for the vital organs of the chest, including the heart and lungs, and supports the shoulder girdle and upper limbs. It also plays a crucial role in respiration.

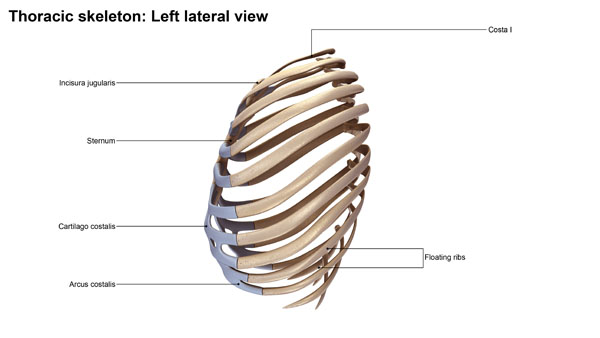

The image depicts the left lateral view of the thoracic skeleton, highlighting the arrangement and relationship of the ribs to the sternum. The labeled parts provide insight into the structure and function of the thoracic cage.

Costa I: Indicates the first rib, which is typically the most curved and shortest of all the ribs. Its superior surface features grooves for the subclavian artery and vein.

Incisura Jugularis: Also known as the jugular notch, this is the large, visible dip on the superior border of the sternum, which can be palpated between the clavicles.

Sternum: Shown here in profile, the sternum is a long, flat bone situated in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via costal cartilages to form the front of the rib cage.

Cartilago Costalis: The costal cartilage is shown connecting the ribs to the sternum. These cartilages contribute to the elasticity and expansion capacity of the rib cage during respiration.

Arcus Costalis: Refers to the costal arch, a curved structure composed of the cartilages of the false ribs (8-10), which converge and meet at the sternum.

Floating Ribs: The eleventh and twelfth ribs are termed floating ribs because they do not attach to the sternum or the costal arch in the front.

This lateral perspective offers an understanding of how the ribs wrap around the thorax to provide protection, support, and flexibility. The rib cage plays a vital role in respiratory mechanics, expanding and contracting with the muscles of respiration to facilitate breathing.

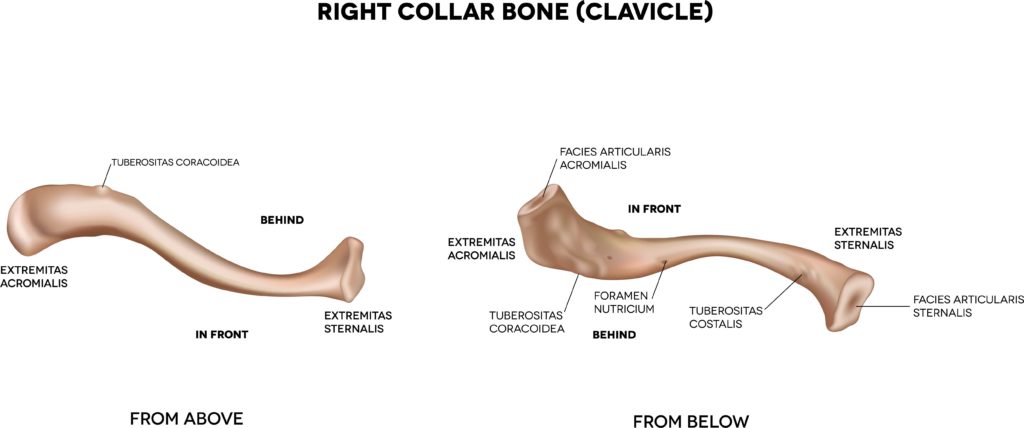

This image presents the anatomy of the right clavicle, or collarbone, viewed from two different perspectives: from above and from below. The clavicle is a long bone that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum or breastbone.

Looking at the view from above, we see the lateral end of the clavicle, which is the part closest to the shoulder. This end is characterized by a roughened patch, the conoid tubercle, towards its posterior aspect, and the trapezoid line running forward from it. These features serve as attachment points for ligaments of the shoulder. The acromial extremity, or the end that articulates with the acromion of the scapula, is flatter and broader than the medial end.

On the medial or sternal end, the clavicle is rounded and articulates with the manubrium of the sternum, forming one part of the sternoclavicular joint. This joint allows for a wide range of movements for the shoulder girdle.

Turning to the view from below, the subclavian groove is visible, which accommodates the subclavius muscle and is an important feature for the neurovascular bundle that includes the subclavian artery and vein. The costal tuberosity for the costoclavicular ligament, which is important for the stability of the sternoclavicular joint, is also seen here.

Both views emphasize the S-shaped curve of the clavicle, which allows for the bone’s strength and resilience, dispersing the mechanical stress that occurs during movement of the shoulders and arms. The bone’s structure reflects its functions, serving as an attachment site for muscles, ligaments, and acting as a support for the shoulder.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Abdominal Cavity | Refers to the space within the abdomen that houses the major organs of digestion and excretion. It is bounded by the abdominal muscles and the pelvic floor. |

| Acromial Extremity | The lateral, flatter, and broader end of the clavicle that articulates with the acromion of the scapula. |

| Aponeurosis | A fibrous sheet or flat, broad tendon that serves as a tendon to attach muscles to the bone, serving as an attachment point for muscles. |

| Arcus Costalis | The costal arch, a curved structure composed of the cartilages of the false ribs (8-10) that converge and meet at the sternum. |

| Cartilago Costalis | Costal cartilage, connecting the ribs to the sternum and contributing to the elasticity and expansion capacity of the rib cage during respiration. |

| Clavicular Notches | The articulation points on the sternum where it connects with the clavicles (collarbones). |

| Conoid Tubercle | A roughened patch on the posterior aspect of the lateral end of the clavicle, serving as an attachment point for ligaments of the shoulder. |

| Corpus Sterni | The body of the sternum, the longest part of the sternum, providing attachment points for ribs two through seven. |

| Costa I | Indicates the first rib, which is the most curved and shortest of all ribs, with grooves for the subclavian artery and vein. |

| External Oblique | A pair of broad, thin muscles located on the lateral and anterior parts of the abdomen, responsible for movements of the trunk, including flexing the spine, twisting the waist, and compressing the abdominal wall. |

| Floating Ribs | The last two ribs (11, 12) that do not connect to the sternum or to other ribs' cartilage, ending in the posterior abdominal wall. |

| Incisura Jugularis | Also known as the jugular notch, a large, visible dip on the superior border of the sternum, palpable between the clavicles. |

| Internal Oblique | Muscles located beneath the external obliques, running perpendicular to them and assisting in trunk rotation, lateral flexion, and compressing the abdominal contents. |

| Jugular Notch | The central indentation at the superior end of the sternum, palpable at the base of the neck between the collarbones. |

| Linea Alba | A narrow band of connective tissue that runs down the midline of the abdomen, separating the rectus abdominis muscles and providing an attachment point for other abdominal muscles. |

| Manubrium | The upper part of the sternum, articulating with the clavicles and the first pair of ribs. |

| Pectoralis Major | A prominent muscle of the upper chest involved in movements of the shoulder joint, including flexing, adducting, and medially rotating the humerus. |

| Pectoralis Minor | A thin, triangular muscle beneath the pectoralis major, involved in movements of the scapula, including downward rotation, depression, and protraction. |

| Processus Xiphoideus | The xiphoid process, the smallest and most variable part of the sternum, providing an attachment for the diaphragm and other abdominal muscles. |

| Rectus Abdominis | A paired muscle running vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the abdomen, responsible for flexing the spine and stabilizing the pelvis, known for its “six-pack” appearance due to tendinous inscriptions. |

| Serratus Anterior | A fan-shaped muscle originating from the first to the eighth or ninth ribs and inserting along the medial border of the scapula, important for the protraction and upward rotation of the shoulder blade. |

| Sternum | The flat bone forming the anterior part of the rib cage, composed of the manubrium, body, and xiphoid process, serving as an attachment point for several ribs and muscles of the chest. |

| Subclavian Groove | A groove on the inferior aspect of the clavicle that accommodates the subclavius muscle, important for the neurovascular bundle including the subclavian artery and vein. |

| Thoracic Cage | The structure formed by the ribs, thoracic vertebrae, and sternum, protecting vital organs and serving as an attachment site for muscles. |

| Trapezoid Line | A feature on the lateral end of the clavicle running forward from the conoid tubercle, serving as an attachment point for ligaments. |

| True Ribs | The first seven ribs that attach directly to the sternum via their costal cartilages. |

| Vertebral Column | The central skeletal structure extending from the base of the skull to the pelvis, serving as the main structural support of the body and housing the spinal cord. |

| Xiphoid Process | The small, cartilaginous projection at the lower end of the sternum, becoming ossified in adults. |