Table of Contents

Cervical Spine: Posterior View

The image presented is a posterior view of the cervical vertebrae, which constitute the uppermost portion of the vertebral column. This section of the vertebral column is critical for supporting the skull, facilitating blood flow to the brain via the vertebral arteries, and allowing a wide range of head movements.

At the top, we see the atlas, labeled as C1, which is unique among the cervical vertebrae for its ring-like shape and absence of a body. It articulates with the occipital condyles of the skull, allowing for nodding movements. The axis, C2, is distinguished by the dens, or odontoid process, which protrudes upward to form a pivot point around which the atlas and attached skull can rotate, providing the motion for turning the head side to side.

Each vertebra from C3 to C7 shows a similar characteristic anatomy with slight variations in size and shape. The superior and inferior articular processes are where adjacent vertebrae articulate with each other, allowing for the flexibility of the neck. The transverse processes serve as attachment points for muscles and ligaments and also contain the foramen for the vertebral arteries. The spinous processes, which project posteriorly, provide leverage for the muscles and ligaments that move and stabilize the spine.

The groove for the vertebral artery, present on the transverse processes of the atlas, is particularly important as it accommodates the vertebral arteries that ascend to the brain. This pathway is crucial for maintaining cerebral circulation. The sulcus for the spinal nerve indicates the location where the spinal nerves exit the spinal column, and these nerves are responsible for transmitting sensory and motor signals to and from the neck and arms.

This intricate structure of the cervical spine illustrates the complexity of the human skeletal system, designed for both support and mobility.

Cervical Vertebrae Anatomy

This illustration provides a lateral view of the cervical vertebrae within the context of their placement in the human neck. To the left, we see the cervical section of the spine as it would be positioned in the body, with the vertebrae aligned and intervertebral discs shown in blue between them, highlighting the cushioning they provide.

To the right, individual vertebrae are displayed, giving us a closer look at their unique structures:

The “Atlas,” or the first cervical vertebra (C1), is shown at the top. It has a ring-like shape, which is distinctive and allows for the support of the skull. This vertebra lacks a body and instead forms a joint with the occipital bone at the base of the skull, allowing for the nodding motion of the head.

The “Axis,” or the second cervical vertebra (C2), is depicted below the atlas. Its most prominent feature is the dens (odontoid process), which extends upward to pivot inside the atlas, enabling the rotation of the head.

The seventh cervical vertebra (C7) is shown at the bottom and is notable for its long and prominent spinous process, which is palpable at the base of the neck and is commonly referred to as the “vertebral prominence.”

These vertebrae are integral to the neck’s structure and function, allowing for a range of motions while also protecting the spinal cord and supporting the head’s weight. The cervical spine’s ability to support and move the skull is made possible by the unique characteristics of each vertebra and the intervertebral discs’ shock-absorbing qualities.

Different Views of the Cervical Vertebra

In this illustration, we’re examining the cervical vertebrae, which are the uppermost vertebrae of the spinal column. There are three distinct cervical vertebrae highlighted here: the atlas, the axis, and a typical cervical vertebra, likely representing the seventh cervical vertebra given its larger size and more prominent spinous process.

The atlas, known as the first cervical vertebra (C1), is unique in that it does not have a body or spinous process. It has a ring-like formation, with an anterior and posterior arch. The anterior arch contains the fovea for the dens (odontoid process) of the axis, which is the second cervical vertebra (C2). The atlas supports the globe of the head and allows for the ‘yes’ motion of nodding the head.

The axis is characterized by the dens, which protrudes upward and articulates with the atlas. This structure allows for the ‘no’ motion or rotation of the head. The axis has a more typical vertebral structure with a body, spinous process, and vertebral foramen.

The seventh cervical vertebra, often noted for its prominent spinous process which can be palpated at the base of the neck, resembles the typical structure of most vertebrae. It includes a vertebral body, transverse processes with transverse foramina (which in cervical vertebrae transmit the vertebral arteries), as well as a spinous process which serves as an attachment for muscles and ligaments.

The vertebral body of each vertebra is the thick anterior portion that provides strength to the vertebral column and supports body weight. The transverse processes protrude laterally and serve as attachment sites for muscles and ligaments. The vertebral foramen is the central hole through which the spinal cord passes. The spinous process extends posteriorly and is easily felt through the skin at the back of the neck. The articulating surfaces, the upper and lower articular surfaces, are where each vertebra forms joints with the vertebrae above and below.

This arrangement of vertebrae is critical for protecting the spinal cord, providing a pivot for the movement of the head, and allowing the passage of important arteries to the brain. The design of these bones reflects the balance between mobility and stability required in the cervical region of the spine.

Atlas and Axis Vertebral Anatomy

The image showcases two of the most superior cervical vertebrae: the atlas (C1) and the axis (C2). These structures are crucial for the rotation and support of the skull.

The atlas (C1) is the uppermost vertebra and lacks a body, distinguishing it from other vertebrae. It is ring-like and designed to support the skull. The atlas is unique in its articulation with the skull, allowing for the nodding motion of the head.

Below the atlas is the axis (C2), which is characterized by the odontoid process, also known as the dens. This process projects upward and serves as a pivot point for the atlas, enabling the head to rotate from side to side. This rotation is what allows you to turn your head to look left or right.

The body of the axis is broader than its superior counterpart and resembles more of the typical vertebrae found further down the spinal column. The inferior articular process of the axis articulates with the third cervical vertebra, allowing for continuity in the vertebral column.

The anterior articular surface is where the atlas and axis come into contact, permitting the nodding and rotational movements that are so essential for head motion. This precise alignment and interaction between the atlas and axis are fundamental to the cervical spine’s range of motion and the support of the head.

Superior View of the Vertebral Body

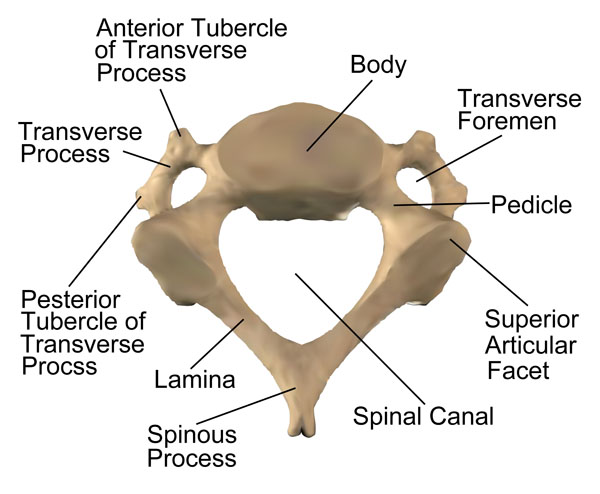

The image displays a cervical vertebra from a superior or axial view, which is the perspective you would have if you were looking down through the top of the spinal column.

At the center of the vertebra is the vertebral body, a robust, drum-shaped structure that supports the weight and distributes loads through the spine. The body is the anterior (front) part of the vertebra.

Encircling the vertebral body is the vertebral arch, consisting of several parts. The pedicles are short, stout processes that project posteriorly from the vertebral body to meet the laminae, which are flat plates that fuse to complete the arch. Together, the pedicles and laminae define the perimeter of the spinal canal, a bony channel that encases and protects the spinal cord.

Extending out laterally from the arch are the transverse processes. Each transverse process has an anterior and a posterior tubercle. These processes serve as attachment sites for muscles and ligaments and contribute to the articulation with the ribs in thoracic vertebrae (which are not visible here as this is a cervical vertebra).

At the back of the vertebra, you’ll find the spinous process, which protrudes posteriorly and serves as a lever for muscles and ligaments that move and stabilize the spine.

On the upper surface of the arch, there are two superior articular facets. These smooth, flat areas are part of the joints between the vertebrae, allowing for movement and providing stability.

Lastly, the transverse foramen, unique to cervical vertebrae, is an opening on each transverse process through which the vertebral arteries and veins, as well as certain nerves, pass. This foramen is particularly important as it allows for the passage of the vertebral artery on its way to the brain.